T H E H A M I L T O N S T O N E R E V I E W

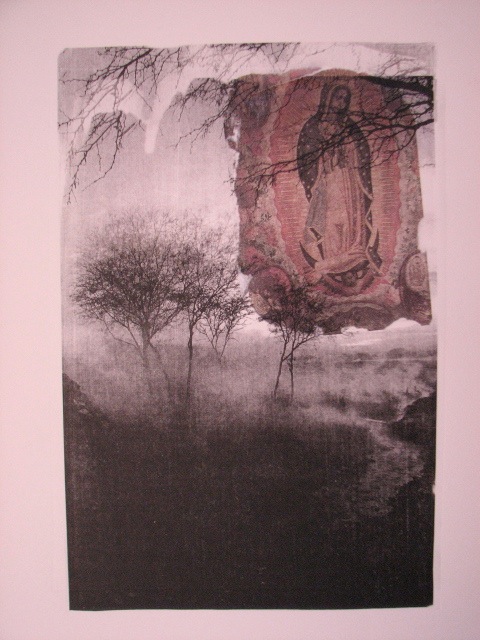

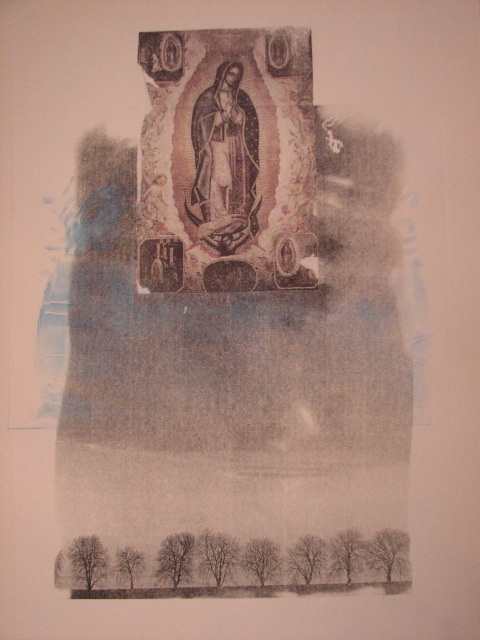

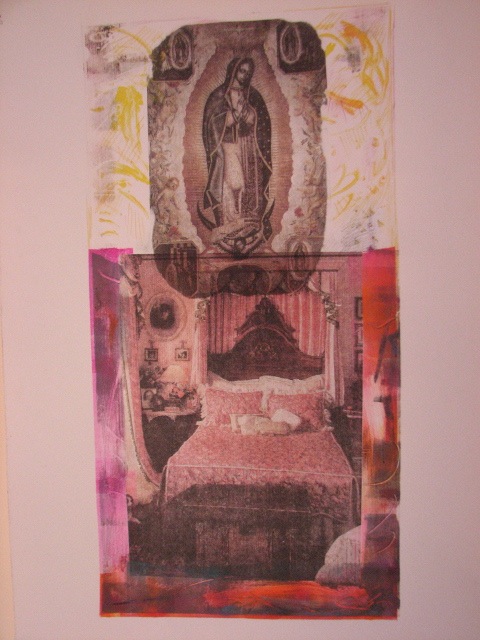

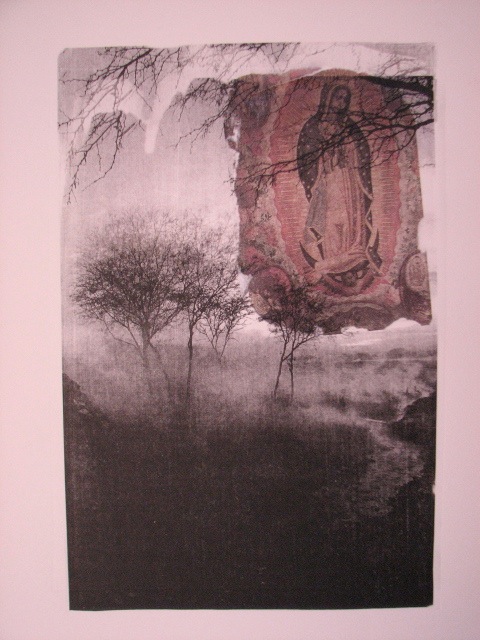

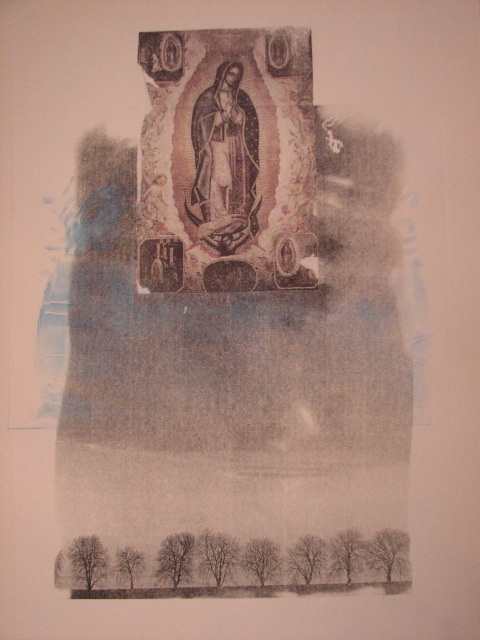

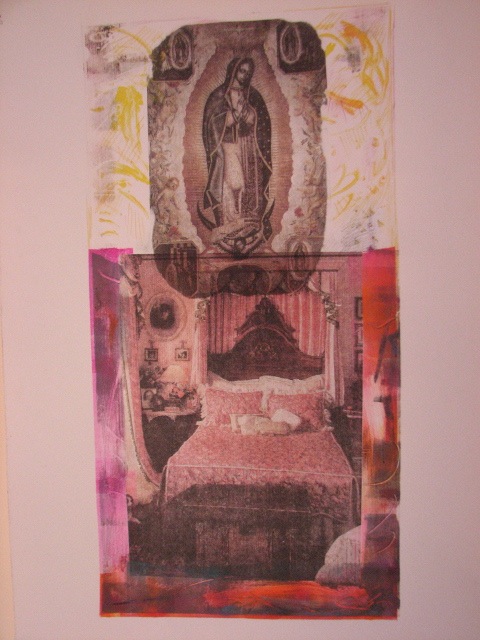

Virgens de Guadalupe by Lynda Schor

Issue # 42 Spring 2020

Poetry

Carol Alexander

Agape

You had a dousing stick knobbed with a mantis head

to find a wallow thick in nascent spring

streaky with beginnings, piqued by the sun's swarm,

a crush of pulpy twigs, rotten veins.

The gilled originals of newt and frog fed there

in mossy, lung-less forms, shivery and vague in the demotic pond.

Light phased them into gold though what they were in themselves

you didn't know. Maybe sad monsters or harbingers. Rainbows trailed the hushpuppies, broke over jagged rock.

Who grows nothing from its source contemplates nothingness,

filches from a hedge a bird's egg drab as dirt, you've the morals of a fox,

taking things unexacting and defenseless as the simplest nouns,

shapes akin to fish pearls in this quenchless mud.

A confusion of magic and mystery—

Prospero breaking his stick.

When it seems impossible to love the world enough as it is and will be,

you think of transformations everywhere—

that good relentlessness, a myriad opening mouths.

The Idea of Valley

Laid half-bare, by winter disarmed,

translucence of shirred pond ice.

With necks like the handles of amphorae,

a crushed velvet shine, geese churning urgency,

hardscrabble creatures un-compassed, elapse: pass by.

Want and disbelief, the knocking at hollow trees—

today this city far from a yellow valley abandoned more.

Mooning trucks roll by; rain, the intensifier,

most green, saturates beneath a wave of itself

while a patch of weed bleeds tawny

in the sluice of old snow. A delta of found things,

a vernacular of sweet and rust.

And beyond the horse guard hardens to bronze, season of patina

where the reservoir divides from blackened muck;

the alluvial impulse of this land backing up,

fistfuls of silt, suckers bleeding flesh, bodies made to disappear.

See the bloat of floating scum, hands clasped.

Remember the elementary stroke, breast to ellipse,

lifting you over the river's skin, and how a valley rustles

in the long growing season. How it stays yellow and stays.

Pacemaker

The brain is meant to give in last.

Mad buccaneer, sometime you will run aground and let us weep.

Around a tactful corner, evening staff keeps the log.

Drivers smoke on the path that leads to the convent deer park

and within ashcans, blackened troughs of day-old food, crows camouflage.

A corpus lies shrunken and remote, wouldn't wish to be displayed

for all the chant and incense though Pascal's Night of Fire would please the nuns.

All else outlasts— stained cotton sheets tucked shroud-like,

canned symphony of a radio, a thrum that is the pattern of electrodes,

but what is the intransitive warmth of a sense memory? She recedes into a sea of ice.

Underground, rootless rhizomes sprout from an array of organs;

it's still summer with its frail archaeology of light, its citrus scent and ruins.

Will death weigh so little at the end—

water has no shadow, only a directional, glancing shift.

Tony Beyer

Father again

thinking of him

as I do too often

while there are others still alive

who could use my attention

yet it is his face

behind my face in the mirror

his hands holding

my cup or my book

some of his language adheres

shared with a wan grin

or regulation laughter

among my brothers

his world of brogues

and Gladstone bags

two-bob bets on the double

has departed with him

whatever his regrets were

left behind like his homeland

his promising future

his inconsistent past.

Nature morte

1

a table top many elbows have rubbed

to a sheen or patina like aubergine skin

and on it rough-husked bread and a wedge

of cheese slightly crumbly at the apex

a flask as well half full of amber light

attended by plain household glasses

that fit comfortably in the hand

and a knife and napkin just this minute put down

and so it shall remain now the painter

and his friends have toasted its completion

and left the room a moment a century ago

possibly to walk outside in the cooling dusk

talking together about anything but works of art

which at their least hang immobile on a wall

in the presence of other works and walls

until the eye arrives to waken them

2

when Lazarus returned from the dead

his eyes had changed colour

and his hands were always afterwards

pallid and thin

he carried about him the scent of dry stone

and his gaze seemed somehow

to funnel the eyesight of something beyond him

more powerful and more obscure

those who had known him before

even those who loved him

could not find it in themselves to do so now

silent in the company of his silences

it was as if a tension

like that of a membrane surrounding a gland

had split partly but not opened

permitting too little of what was inside to be seen

because it would come to them sooner or later

everyone wanted to ask him what death was like

but he being healed of the worst of ills

persisted in telling them nothing

nor did he speak again of his rescuer

for whose eventual fate his was a rehearsal

both of them men without fear

whom nothing on earth could threaten

3

once rain water has settled in the tank

its cold feet

bedded in sludge and leaf mould

its upper levels ice-clear

I use a length of old hose

to siphon it onto the hibiscus

high to low

one of the simple miracles of physics

and while there may be bacterial reasons

not to do this

surely nothing that rots can hurt the earth

made up as it is of rot and renewal

hard droughty summers

and long nights scarred by the moon

our place of the utterly ordinary

becoming scarcer

Still teaching at 71

I was already old

before these students were born

so quite recent events

on my time-scale

Bill Clinton 9/11

the Bali bombing

are as obscure as Mafeking

let alone my childhood

just after the middle

of last century

my schooling in the age

of canes and cold showers

a lifetime’s experience

about as interesting

as a garage sale to them

and good on them too

at least they don’t have to put up

with ancient codgers

banging on about the war

or sugarbag underpants

or how many family members

shared the lid of the dad’s boiled egg

their world is the future

I won’t see

enigmatic and unaccountable

as my past to them

I wish they could have met

my grandfather

born in the 1800s

puzzled by the 1900s

who knew better than any of us

how to go about his days

Charles Cantrell

The Last Rehearsal

If leaves could speak, wind dropping

syllables through branches.

If the stars were white spiders

scattered on a black sheet of infinite black

tar paper over tin,

what would you turn to?

If summer could fall apart like a steer carcass

at the edge of a wheat field in a wind storm.

If creatures that maneuver their small bodies

and brief lives could live at weed-root.

If you’d like the months to accelerate so you could see

the plum blossom before the purple blush

of skin right at the green nub of fruit,

what would any of this do for you?

To think that the non-human is close to human

rings of delusion and can be dangerous.

Clouds don’t have sleeves, the earth doesn’t beat

like a heart, flowers don’t stick out tongues,

grass doesn’t sing or bend like the back

of a beloved. It’s the wind, with no hands,

no face, no teeth, which can break you.

No Resolution

after Michael Benedikt

The feelings go up into the air

like birds who know the air

better than we do. What feelings?

Someone’s tears fall in cold air.

Someone needs to know what happened.

The person weeping is wearing a sheepskin coat. Despair

blows around her, colder than mere wind.

Maybe someone hurt her. Up in the air

are the words she wants to choke out. Someone should

go to her and find out what happened. The chilly air

by the roadside near some woods

is no place to linger, especially in the air

of not knowing her full story. What if she cannot say

what really happened or why? Can’t you air

your feelings? you want to say. Please talk to me.

Birds in the woods are singing. They own the air.

Someone better be holding that woman now, whether

or not they played a part in what hurt her in the dark air.

Culvert

after Aron Wiesenfeld’s “Surfing Bird”

The drain pipe is almost three times the height

of the girl standing near the entrance,

facing the dark end.

Why is she here?

She wears no shoes. Just a trickle of water,

almost as still as the girl, from the opening.

Thin dress to her knees. You can barely see

her arms. If water were to rush her way,

would she hear it coming?

It’s a gray and dark world here.

Even the bushes to her right are hazy

as gauze. All I know is darkness

and light aren’t her language,

despite their duality in the world.

The girl’s too young to know that.

Maybe the immensity drew her in.

Maybe it’s hot out, and the breeze

pulled her inside. The iron cylinder

surrounding her is cool. Air moves

from the far end. To be this alone

and quiet and fearless, facing a huge tunnel—

and no way to tell what’s at the other end,

even whatever she imagines may be there: car,

man, log jam, or hundreds of white

butterflies sipping from a stream

that winds its way to the entrance.

In the Woods

When someone left me for no

apparent reason I could figure,

I wanted to understand. I could reduce

the whole matter to a wasp on my window pane.

Would it want to sting me? And why?

From across the treetops past my cabin,

I can see the city lights. I left there

long ago. No hermit like Thoreau,

I don’t grow beans or corn, nor take

long walks in the woods, touch bark

and sigh, or wonder what my boots crinkle

or kill. I visit the city now and again

and always look in a store window

at cashmere sweaters, like the one she wore.

Her eyes are the color of chicory petals

in sidewalk cracks near a barbershop.

I’ve been among wildflowers long enough

to know their fate, perennial or not.

My garden, temporary as it is, is regal

and supreme. The woods inside me are hard

on the outside, but soft on the inside.

What they believe in, I cannot tell.

David R. Cravens

Southerners

Kenny Grahame at five years

lost his mother to fever

was orphaned by his father

then deprived university

by a miserly calvinist uncle

who sentenced him thirty years

(gavel cracked in half)

served in the Bank of England

incorrigible inmates

with pitbulls tied to desks

(for dogfights after work)

the ghylls and wealds

meadows and Berkshire downs

served as his escape—

upon return to the house

he’d recite to Alastair

(his nervous purblind child)

adventures of a mole and a rat

a badger and a boastful toad—

Kenneth’s role was Mole

Alastair was Toad – id incarnate

Rat was Edward Atky

& Badger was William Henley

Grahame’s previous editor

who’d written “Invictus”

future darling of Tim McVeigh

as well as Nelson Mandela

some ten years later

Alan Milne was on the Somme

a putrid wasteland of casualty i

relentless bombardment

& hungry flies on bloated corpses

when he’d ask of new recruits

if they’d read The Wind in the Willows

his litmus test of character ii

& it was the Somme

that nurtured a pacifism

that bled into Winnie-the-Pooh—

a whizz-bang near Mametz Wood

near thwarted Pooh Bear

even before his conception

but Alan escaped the Front

begat a son – Christopher Robin

& bought a home in Sussex

at the edge of Ashdown Forest—

when he and Christopher

(and the boy’s prized bear)

were walking nearby spinneys

& heathlands of gorse and heather

Richard Adams – just west

was taken into Newbury

saw a peddler skinning a rabbit—

gibbeted others stiff and empty

hung from the man’s makeshift cart

& the boy burst into tears

(barely consoled by his mum)

trauma that nurtured a pattern

a motive of retreat iii

& he too’d withdraw to the downs

their woundworts and cowslips

(copses of bluebell and hazel)

before being sent to boarding school

where beaten and beset

by bullies and pervert teachers

decidedly lost in the Wild Wood

Mole and Ratty seek refuge

deep in Badger’s den

from cold and snow and darkness

& vulgar stoats and weasels

(of bolshevistic bent)

where Mole tells Badger

in the warm firelit kitchen

that being underground

begets bearing and security iv

tenders an equanimity—

for what happens up top

will await your return

& once rested and fed

they depart through adjacent crypts

vaulting ribbed of id and ego

to emerge again to conscious

river just within sight

Wild Wood in perspective—

barbaricum outside the gates

the book begins with flight

Mole’s release

up into the world without

yet later that midwinter

tucked in his bunk

he looks round his room

firelight dancing on treasures

(panoply of journeys afar)

& reflects the author’s perspective

in that Grahame’s dreams

were often of a flat

dear and familiar and safe

in the midst of a raucous London

yet carefully sealed away

soft chair by fireside

shelves of his favorite books

a few beloved paintings

always a sense of homecoming

peace and possession

sun and air – adventure and veld

(Seafarer enchantment)

are well and good – vital moreover

for even David Morell

lifted his hero John Rambo

from the first chapter of Pooh v

but an anchoring

(something for to come back) vi

comfort – safety – warmth of hearth

love and unspoiled friendship

are equally of bearing—

for the true sense of hiraeth

exemplified by the families

nestled warmly in their dwellings

that Mole and Ratty spied

on their winter village shortcut

may truly be understood

only by those Grahames

who’ve known so little security

or the Adamses and Milnes

who’ve traveled so far

from the sanctum they’ve known vii

victorian graspers of dogma

& judicious propriety

pushed Alice down a rabbit hole

& the Owl and the Pussycat out to sea

sent Alan Milne to the trenches

& ten million boys to their deaths—

talk of paradise starts

only when something’s been lost

(or in the process thereof)

& in addition to his room

Kenneth often dreamt of Oxford

(a wound that wouldn’t heal)

though he’d avoided it since youth

when he’d floated the Thames—

Port Meadow as merestone

Grahame’s meridian

for past it lay noise and jetsam

motorcar and railroad

dragons’ teeth of oppression

that threatened a landed gentry

(a moribund aristocracy)

factories and steam and combustion

(bearing a building of rooks)

Milne saw the first half of carnage

landscape destroyed by the Western Front

begetting a lost generation

& Adams felt the tractors coming viii

just like in Fiver’s dream—

so he left for the second war

saw the promised peace of industry

turn systematic genocide

nature red in tooth and claw

(fifty-six million dead this time)

thus had Sutch & Martin

taken care to plug the holes

before gassing Sandleford Warren

fantasy as bastion – canton

of both venture and security

assuagement in both

the contemplative or active life

in sinusoidal equity—

anthropos and mythos

each giving way to the other

meden again – escape from the other

each again the soul of the other

Alastair Grahame remained aloft

never withdrew underground

(just like Mr Toad)

nor was the surface a place for either—

for on a spring evening in ’20

at his father’s beloved Oxford

Alastair walked across Port Meadow

& ended his life on the railway—

Adams was born that next Sunday

(down in Wash Common)

& later on that summer

Christopher Robin was born in Chelsea

& upon his first birthday

was given the bear from Harrods

a map of Africa hung on the wall

when Christopher Robin was six

& he and Pooh would follow the Arabs

from oasis to oasis—

this was the year Milne wrote of his son…

when I was five

I was just alive…

but now I am six

I’m as clever as clever

so I think I’ll be six now

for ever and ever

but Christopher Robin didn’t stay six

Christopher Robin got older

& Christopher Robin went off to war

to escape Christopher Robin

& as a sapper with the 56th

(near the border of Benghazi)

he’d gazed in wonder at baby larks

nested by the husk of a burnt German tank

chorography of life and death

a balance unbecoming

suggestive of Cowslip’s warren

for utopia begs holocaust—

flayrah necessitates blood

upon Christopher’s return

much the Hundred Acre was gone

even the ancient beech

where Owl had kept his home—

he’d arrived sullen anyway

reluctantly finishing Cambridge

began to resent his father

& despise Winnie-the-Pooh

felt the books had stolen his name

leaving little in return—

he drifted from his parents

& Alan by ’55 had written of his son…

I lost him years ago ix

one last time the boy came home

to attend his father’s wake

then never again saw his mother

(not even on her deathbed)

for she’d even taken down his bust

had it buried in the wood

so as to never again see his face

Adams too returned from the war

& also come home changed

he’d had a friend called Paddy

& a major named John Gifford—

together they’d pushed to Arnhem

(Gifford and Adams)

when Paddy was ambushed at Oosterbeek—

Paddy’d grabbed a bren gun

(along with some clips)

dove in a ditch like a kern

knocking out rounds at the Huns—

yelling orders the while

for his men to escape through the woods x

(he’d saved most every man)

& with no known kith nor kin

they buried him there in Gelderland

then auctioned off his few things

on arriving back at Oxford

Adams found that his other mates

neither’d survived the war—

& his heart went with the thousand

he withdrew into domesticity

civil service at Whitchurch

would walk the Hampshire downs

& thinking back to that cart

began contriving a tale

that he’d soon tell his daughters

of a destitute band of rabbits

looking to found a new warren

& he made his friends immortal—

Hazel is John Gifford

& Bigwig’s Paddy Kavanagh

they continue to live with their company

in the pages of Watership Down

so for those of us who are lost

or mired in confusion

let us wander worlds that should be

seek nature for redress

be it literature or riverside

or woodlands of wish-fulfillment

of forestborn childhoods never had

where through life’s troughs

I’ll escape with Rat and Mole

to the reaches of the willowed Thames

retreat to Watership Down

with Hazel and Bigwig and Fiver

& scout the Hundred Acre

with Pooh and Christopher Robin—

come with us should you wish

to that enchanted place

at the top of the forest

where a little boy and his bear

will always be playing

but too let’s not forget that child

mired in excrement

& cringing in terror and pain

in the corner of a cellar—

true – the child is under Omelas

but it’s also beneath that enchanted spot

in the reaches of certain souls

of men like Richard Adams

Kenneth Grahame and A. A. Milne—

lest not we exhaust our nepenthe

& forget the charge of good deeds

i “There was a quiet boy in our reserve battalion, fresh from school; the younger of two sons. We went out to France together to join the same service battalion of the regiment, and on the way over I got to know him a little more closely than was possible before. His elder brother had been killed a few months earlier, and he, as the only remaining child, was rather pathetically dear to his father and mother. Indeed (and you may laugh or cry as you will), they had bought for him an under-garment of chain-mail, such as had been worn in the Middle Ages to guard against unfriendly daggers, and was now sold to over-loving mothers as likely to turn a bayonet-thrust or keep off a stray fragment of shell; as, I suppose, it might have done. He was much embarrassed by this parting gift, and though, true to his promise, he was taking it to France with him, he did not know whether he ought to wear it. I suppose that, being fresh from school, he felt it to be ‘unsporting’; something not quite done; perhaps, even, a little cowardly. His young mind was torn between his promise to his mother and his hatred of the unusual. He asked my advice: charmingly, ingenuously, pathetically. I told him to wear it; and to tell his mother that he was wearing it; and to tell her how safe it made him feel, and how certain of coming back to her. I do not know whether he took my advice. There was other, and perhaps better, council available when we got to our new battalion. Anyway it didn’t matter; for on the evening when we first came within reach of the battle-zone, just as he was settling down to his tea, a crump came over and blew him to pieces…”

~A.A. Milne, Peace with Honour

ii “One does not argue about The Wind in the Willows. The young man gives it to the girl with whom he is in love, and if she does not like it, asks her to return his letters. The older man tries it on his nephew, and alters his will accordingly. The book is a test of character … When you sit down to it, don’t be so ridiculous as to suppose that you are sitting in judgment on my taste, or on the art of Kenneth Grahame. You are merely sitting in judgment on yourself.”

~A.A. Milne, from an introduction to The Wind in the Willows

iii “There was no lack of fairly wealthy (and some really wealthy) families round Newbury. Several of these regularly gave children’s parties, and naturally the family doctor’s children were invited. As I was so much younger than my sister and brother, I used to get asked to different parties, for smaller children – alone. Of course, my father didn’t like the invitations to be refused. If it were Ann’s or Mary’s party this wasn’t so bad, but some of the big parties at wealthy houses, among a crowd of rich children who were mostly strangers, were unnerving – quite as bad as a parachute jump was to prove later. I was socially timid, used to solitary play, and nervously uneasy among the rather reserved and self-possessed boys and girls, well equipped to fulfil the roles expected of upper middle-class children in those days. For the most part I got on badly.

One of these parties was for me the occasion of a genuine Freudian trauma, the origin of a behaviour pattern of cracking under stress which has remained with me all my life: I know it well and can spot it whenever it turns up. This was a big party, given by the parents of a boy I hardly knew (he later kept wicket for Eaton), and it was fancy-dress. I went as a Red Indian, though you could hardly have guessed it. The costume, such as it was, was old and shabby and had been lying in some cupboard since before I was born. It did fit, but what it amounted to was a crumpled jacket and trousers of thin, brown cloth, edged with strips of red and blue canvas. You couldn’t wear it with any swank, which is surly the whole point of fancy dress. I could just about get by in it – and perhaps not even quite that. We hadn’t the money for smart fancy dress.

I knew hardly anybody at the party. Most of the children were a little older than I. There were some splendid costumes. I remember a fairy, with wings and starry wand, to take your breath away. There was also another Red Indian, finely attired, with a tomahawk and a head-dress of coloured feathers half-way down his back. He didn’t speak to me.

After a while we were assembled to watch the Punch and Judy show. I had never seen this before and had no idea what I was in for – a series of brutal and savage murders. I watched in mounting panic. Surely there must be some way out of this? Eventually Punch took the baby, Judy exited and Punch began banging the baby’s head against the side of the box,

That did it. I was quite near the back. I got up and slipped out of the room. I didn’t care where I went, as long as it was away from Mr Punch. No one seemed to have noticed me go, and in the hall there was no one about. I went upstairs, into a long, cool, empty corridor with closed doors on either side. It seemed to me that one would be as good as another. By this time I was in such a state of horror that I had the fancy that it was quite likely that Mr Punch would come and get me. Credo quia impossibile est. I could, of course, have been reasoned out of this, but there was no one to do it. Since then I have seen grown-up people give way to fears as absurd.

I opened a door at random. It was a bedroom, with the bed, head to the wall, aligned just to the left of the hinge side of the door. I got between the bed and the door, and then pulled the door wide, to an obtuse angle, till it touched the bed, thus forming a thin, hollow triangle – door, bed, wall. Here I felt myself in a place of refuge, a place of hiding and protection – a womb, of course, as we have all learned to think since then.

‘Aha!’ I kept murmuring silently to myself. ‘Mr Punch can’t get me here! Mr Punch can’t get me here!’ I had no idea of consequences: I mean, any idea that obviously this couldn’t continue indefinitely. I just felt that where I was, I was safe from Mr Punch. That was enough.

I stayed put and never made a sound. I don’t know why, since the calling voices were kind enough. I suppose my fear had somehow extended to include all the strangers in the house. Also, as I think we all recognize, panics and escapades possess a kind of in-built impetus. It is like being on a roller-coaster. You can’t get off. Someone else has to stop it.

Eventually someone – a lady – came into the room again, swung back the door and found me. They were all far too much relieved to be cross, and also, of course, I was their guest. I can’t remember the rest of the affair, though I remember trying to explain my fear. I think I just rejoined the party, which by now had got on to ‘Nuts in May’, ‘Hunt the Slipper’ and similar harmless activities.

But although I was not to realize it consciously for years, something fundamental and seminal had occurred. A behaviour pattern had formed. It might be described like this. First, I knew and accepted that it was possible for me to be genuinely and in all truth driven beyond the point of endurance by something that evidently didn’t bother other people at all (or perhaps something that they could endure). Secondly, I could get out of this by taking solitary action, involving some sort of retreat into hiding; possibly an actual, physical refuge or else an infantile state (illness, breakdown, etc.). Thirdly, if only I could keep it up, heedless of its effect on my standing or reputation, it would get me out of the situation, whatever it may be.

This, however, didn’t turn into a really bad neurosis. My home was much too supportive for that, my family too kind and understanding and the world too full of exciting, happy things. But it had come to stay; and under any relatively heavy strain, up it has been popping ever since; sometimes controlled and pushed back into its cage, sometimes not. Also, the notion of the enclosed refuge has remained as a permanent fantasy. ‘I’m all right: I’m hiding in here.’"

~Richard Adams, The Day Gone By

iv “He won’t know how to shiver in a week or two,” said Hawkbit, with his mouth full. “I feel so much better for this! I’d follow you anywhere, Hazel. I wasn’t myself in the heather that night. It’s bad when you know you can’t get underground. I hope you understand."

~Richard Adams, Watership Down

v ‘“Oh, help!’ said Pooh, as he dropped ten feet on the branch below him.

‘If only I hadn’t—’ he said, as he bounced twenty feet on to the next branch.

‘You see, what I meant to do’, he explained, as he turned head-over-heels, and crashed on to another branch thirty feet below, ‘what I meant to do—’

‘Of course, it was rather—’ he admitted, as he slithered very quickly through the next six branches.

‘It all comes, I suppose’, he decided, as he said good-bye to the last branch, spun round three times, and flew gracefully into a gorse-bush, ‘it all comes of liking honey so much.’”

~A.A. Milne, Winnie-the-Pooh – Chapter One: In Which We Are Introduced to Winnie-the-Pooh and Some Bees, and the Stories Begin

vi “He [Mole] was now in just the frame of mind that the tactful Rat had quietly worked to bring about in him. He saw clearly how plain and simple – how narrow, even – it all was; but clearly, too, how much it all meant to him, and the special value of some such anchorage in one’s existence. He did not at all want to abandon the new life and its splendid spaces, to turn his back on sun and air and all they offered him and creep home and stay there; the upper world was all too strong, it called to him still, even down there, and he knew he must return to the larger stage. But it was good to think he had this to come back to, this place which was all his own, these things which were so glad to see him again and could always be counted upon for the same simple welcome.”

~Kenneth Grahame, The Wind in the Willows

vii “Walking at night I like to come upon the lighted windows of a wayside cottage and to feel that behind the curtains is another world, a world founded by four walls, a world of sight. I long to peer through the windows and I know that even the dullest scene within would to me become high drama. I love especially, returning home, to see the lights of my own house shining. So, I am sure, did the astronauts feel returning from the moon travelling through black space toward a waiting world. Soon they will once more be a part of that world. Soon I will be home, part once more of the indoor world of light and warmth. Such is a dark night.”

~Christopher Robin Milne, The Path Through the Trees

viii “So during the summer of 1939 Oakdene, my beloved and life-long home, was put on the market … [It] was sold, a few weeks after the outbreak of the war, to a middle-aged couple called Balfour, who could not have been nicer to deal with or to have as neighbours. Mr Balfour, not to mince words, was a gentleman, of the same family as Arthur Balfour, the Edwardian Prime Minister. He was cultured, friendly, extremely loquacious and a pleasant man to deal with. Mrs Balfour was also pleasant enough, but had her own ideas about what she wanted to do with the property. Now, I personally began to feel one disadvantage of moving to the Thorns’ adjacent cottage: you had to stand by – without a word, of course – and watch what she did. And what she did, principally, was to fell the trees. Oakdene’s three acres contained plenty of trees, and several of these had individuality and had in effect been landmarks in our lives. We knew every tree in the garden, of course. I could draw a map, now. I have never been able to understand Mrs Balfour’s motive in felling the trees, for having felled them she did nothing more to the sites. She felled the three silver birches along the crest of Bull Banks, and she also felled the Spanish chestnut – which made even my brother wince and express regret. Then she dug up the circular rose garden outside the dining-room windows: but she didn’t convert it to something else. She just dug it up and left a mess.”

~Richard Adams, The Day Gone By

ix “Farewell, Papa … ‘Well’, you will tell yourself, ‘it lasted until he was twelve; they grow up and resent our care for them, they form their own ideas, and think ours old-fashioned. It is natural. But oh, to have that little boy again, whom I used to throw up to the sky, his face laughing down into mine … ’”

~A.A. Milne, It’s Too Late Now

x “With a kind of wry envy, Hazel realized that Bigwig was actually looking forward to meeting the Efrafan assault. He knew he could fight and he meant to show it. He was not thinking of anything else. The hopelessness of their chances had no important place in his thoughts. Even the sound of the digging, clearer already, only set him thinking of the best way to sell his life as dearly as he could."

~Richard Adams, Watership Down

Steven Deutsch

At 10

When

it’s very clear

and very cold

my mind makes room

for recollection.

Images

hidden for fifty

years crisp

as that first step

on snow

flash-sealed

by an unearthly freeze.

I’m ten

and my dad and I

have stepped into

the silence

of an iced-in

avenue.

The sycamore limbs

mummified

in sheathes of clear

crystal.

Just for today

I am

the only son

and even

that first stab

of arctic air

is reason

to rejoice.

Heartland

I

Some soft

summer mornings

we’d take

our little lane

west, on what

our parents

once called

a Sunday drive.

Roads here

were built

for horse

and carriage

and meander

like streams

searching for

a lost river.

When at times

the early fog

takes

possession

of the earth,

we drive

more from

memory

than vision—

secure

in our

obscurity.

II.

This morning

the fog

is thick

as Burma-Shave

and I imagine

an invading

army

padding silently

over the ridge

on elephants

and camels

to await

the blooding

of the sun.

But here

in the heartland,

we’ve little

left

to defend.

The young

and the able

long for more

than mastering

the s-curves

down Shawnee Ridge

and $7.50 an hour

at Burger

Den downtown.

They seem to know

from birth

that all our roads

lead only

to somewhere

else.

Brian Fanelli

Dylan Cool

You are rolling thunder,

one hand raised, ready to crash upon guitar strings.

You are Judas plugging in,

blast of chords powerful enough to rumble the stage.

You are the hum of big amps,

leather jacket cool,

the husk of throaty blues,

the jingle jangle of a new arrangement each show.

You are lyrical mash-up,

Pound and Eliot on the Titanic’s deck,

Shakespeare in the alley with pointed shoes and hat.

You are protest, the voice of Hattie Carroll mopping the bar,

before the crack of a cane against her skull.

You are Rubin Carter punching out of a jail cell.

You are I don’t give a fuck,

still strumming over the boos,

a raspy prophecy about changing times.

You are a puff of black gray hair

rising beneath stage lights like a wisp of smoke,

one final chord echoing late into the night.

Another Decade, Another Protest at Courthouse Square

I'm back at a Courthouse Square holding a No War sign,

this time in Scranton instead of West Chester,

this time Iran instead of Iraq.

I still wear punk rocker black like I did in college,

but zip up my coat to hide the fanged gremlin

on my T-shirt once the cameras point and shoot.

This time, I linger in back, like a teenager at a dance,

trying not to be seen, while a fired radio host declares,

Don't roll over! Agitate! Resist!

I want to ask him what he's been doing

since he's been canned and how he pays the bills.

At 18 I seized the mic, jumped on benches,

shouted, No War in Iraq!

I hear the same chants almost twenty years later-

Tell me what democracy looks like!

This is what democracy looks like!

I repeat the No Blood for Oil slogans,

but my voice is barely a whisper,

maybe because I've been through this before,

maybe because I remember March 2003

when snow soaked my Converse sneakers and numbed my toes.

No matter the marches, the songs we sang,

the police barricades that kept us to one side of the street like cattle,

bombs still leveled Baghdad by mid-month.

I watched in my dorm room and remember how shrieking rockets

looked like fireworks I watched with my family.

It's winter again, mid-January, unseasonably warm.

The sun feels good in my hair, on my hands,

holding another cardboard sign while a teen takes the mic,

tells us that he's about to graduate, that he fears escalation.

The tremble in his voice reminds me of myself

at that same moment when the news reported the potential

for armed conflict in a country reduced to headlines.

Maybe I'm there for him, like those professors were there for me,

to let him know that he's not alone and when he looks back,

years later, during another rally for another war, he can remember

we stood there, defiant under that January sun,

our voices taking flight beneath pointed courthouse spires.

Aaron Fischer

Expatriate Elegy

(for Ilya Shifrin)

“Am I understandable?” you’d ask every three or four

sentences. Your English got better with each shot of vodka

I downed, though the only Russian I can remember

from those years — nietzschevo, a drinking song’s loud chorus.

“Nothing, nothing, nothing!” we’d laugh and shout

and knock back another, your two-bedroom crowded

as a communal apartment in Moscow,

expat cab drivers, concert pianist, mournful au pair in brown.

I’m better at elegy than friendship. “Why did you disappear?”

you asked at my wedding. Ten years of expensive talk

and I still don’t have an answer. Now you’re a ghost,

a few telltale gestures growing less palpable each year,

a voice that barely cuts through the static.

Sing with me: Nietzschevo, nietzschevo, nietzschevo.

Moonrise from a Balcony in Brooklyn

for Anna Fischer and Philip Kalmes

Slowly, deliberately as a Kennedy half

magic’d from a silk top hat, the full moon

clears the banked clouds shrouding Staten Island,

where the mob once ran

the world’s biggest garbage dump — Fresh Kills,

that irony surely lost on no one,

the gulls stacked up like air traffic over JFK,

wheedling and crying like penitents.

In this green era the trash heaps and hummocks are lush

as lawns. Whatever light the cloud cover allows

silvers nature walks, bike paths,

the blind for watching shorebirds. But the gulls

are up to the same thuggish tricks year-round:

bullying each other to drop their scraps.

Lust for Life (MGM: 1956)

The crows in the Van Gogh biopic with Kirk Douglas

deserve an Oscar for best supporting actor,

bedeviling and battering Vincent at his last plein-air

landscape. It’s great box office,

but it’s not true. His final work: the serene

Daubigny’s Garden. Violet-bordered flower bed,

violet cat, his friend’s wife framed by a blue-rinsed

stucco wall. Nothing throbs or threatens

to change shape.

No. Van Gogh has to suffer

for painting the wagon ruts through the wheat

apple green, the wind’s yellow and rust shimmer.

The crows flap and jeer on cue. Vincent

scribbles a few black glyphs on the canvas, staggers

from the easel and puts a bullet in his gut.

Guide to New Jersey

Archetypal East Coast suburb, without the obsessive

planning that makes Levittown look like a printed-

circuit board from the air. Meat-and-potatoes

architecture — low-slung ranches, split-levels perched

above a garage, a few fanciful, steep-gabled Tudors

fit for a bird watcher or small-time Mafiosi,

north Jersey’s favorite sons. Each week, the bucket loaders

tear down a few more, reclaiming the property

for million-dollar McMansions, starter castles

with balustrades borrowed from a Venetian palazzo,

Endura-Stone columns flanking the entrance —

bad taste on a grander scale than the houses

they supplant — mortgaged, silent-majority brick. Only

their vanishing made them worth a second glance.

Night Piece: New Jersey

This far north there’s not much

dark, where the state’s broken flint

arrowhead would be fitted

to the haft, where

acres of refineries glare

like small cities on

the horizon, joined

by the turnpike’s

dazzling river, flare stacks

topped with flame — cobalt,

yolk, white, depending on the crude

being processed. After

the last customer

goes home, the one who lost

her keys and had to call

an Uber, after the night

crew stows the burnisher,

the walk-behind waxer

in the van, the mall

parking lot is shadowless

as a prison yard. Jersey’s

famed barns glow and glitter

all night — Pottery, Tool,

Dress, Candy, Bed, Furniture,

Music — gaudy boxes of

brilliants. And cobra-

hooded security lights buzz

and flicker, flicker and burn

blue-green outside Whole

Foods and Costco, alchemical

fires doubled in the emergency

doors, while diners serve

breakfast round the clock,

the Tick Tock and Times

Square, counters gleaming,

spoons lying on their backs

at the Alibi, bright teardrops

at the bottom of their bowls

that could pass for stars,

if we could see the stars.

Kara Goughnour

Twenty-Four and, Humbly, Bored

It's noon on a Monday and the winds

are nothing short of monstrous,

the whole world a car-crash swirling,

exhaustion the last thing left on our tab.

To the world, we still owe everything,

still need to lay our humble backs

to mattress a hundred times.

To this world, we are still young things,

opting for every option,

peeling away the searing pain

of teenage grieving.

To the world, we are deserving of nothing,

not a breath we don't pull into our own lungs,

not a gust of belief to sweep our doubt away.

Using Chairs as Tables

Build my dried blood into

a new deck, string candles

above like garland made

of day stars dying in the brightness

of astronomical twilight.

Jump from the cityscape

of the snakeplant’s cross-banded erectiles,

buy my cherry casket from Costco

and bury me in the terrarium hanging

in the glazed window pane.

Craft a toe-pinching tiny home

from the blotting coffin clot

of my bit lip, rip out

every ripened lie and hang it

with the dried lavender to keep.

Using the Wendy’s Takeout Window as a Confessional Booth

I am oval sea-palms

sloped forests the length of secrets

{living in leaves}

licked wild —

my disdain sand-colored,

fine hairs beating,

soft swell of root.

My slouching, sea-dark

shadows tapped and steeping,

back stuck with meat hooks

{arranged oval}

like subjects awaiting benediction

like psalms claimed seduction.

Pat Hanahoe-Dosch

What I Know About Death

The dead rise

suck marrow from our bones

own the seconds after a light is turned out

peel our dreams from our nights

like hunters skinning rabbits

exhale through air conditioning vents

and heat exhaust condense into steam rising

from radiators and windows

even roil in slips of fog on a road at sunrise

burst through the dirt of early spring

as the first coils of tulips rising

filter the sun's glare in windows

drip a full moon's glaze over the ocean

rippling and beckoning in the waves' shimmer

They reach through our mirrors

unfurl their claws deep in our lungs

Nels Hanson

Day to Day

At the four horizons low

clouds edged with light

say gently rain is coming.

The wind blows from West

to East and all fallen leaves

fly for the high mountains.

Tule ponds held luminous

fish where deep vineyards,

flowering almonds grow.

At dusk the Coast Range,

soft outline of a woman

dreaming of sea flowers.

Summers sky draws close

and many stars fall from

the watching Milky Way.

As we sleep the waters

in the brimming cistern

capture a passing moon.

Marilyn Humbert

Shadows of Troy

take me back

to Scamander Plain

the ramparts of sloping stone

back to the barrenness

where Hector’s ghost wanders

below Troy’s scarred walls

and to the shallows

between bones of black galleys

beached on the pebble-shore

let me walk

with shadows of soldiers

silver blades gleaming

in the ruins of Troy

your hand brushes mine

my own brave Hector

chasing our dreams

we found love

near the Dardanelles

Alex MacConochie

Wasp Nest

No nest, a momentary festival

And hum: woodchuck’s body splayed in yellow grass,

Length of a nine-year-old’s hesitant, purple

Shadow distant, one ragged paw and the clotted slick fur,

Headless, flies fizzing at its neck, a blood

Dark bloodless hole the gleaming trap

Frames and mommy, why? Split-rotten peach

Thick with wasps and her warning, don’t

Disturb them. And the madly sweet marigolds

Nod, the rusted blue school bus, a tractor

Whirs in the fallow field and it’s because

The groundhogs want to eat his crops, you know.

We grew up in different regions, call the dead

Thing different names. Great-uncle Sal

Still shakes his head at the kitchen table, white beard

Pulling his chin down, smile gentle but the land

Although some young men work it for him, rent it

From him, even across the highway there (a liver

Spotted querulous jab out the wrong

Window) still his despite the pests he… green

Blank, township soccer and lacrosse fields, now.

Assyrian Panels

1

The lion’s body flows from bar to bar

Extending to be shown contained. Its brother,

Hunted in the gypsum field, shrinks down

To extinction behind a sun-flare mane

And Ashurbanipal, the mighty, magnifies

His power in the power that he keeps at bay

You explain and add: of course it’s been so long

Since I learned all this. I love you when you show me

How you look at things. The words expand my throat,

They hammer at my teeth. I say that’s really cool.

2

The placard calls them winged genii,

Antediluvian sages. A palace door’s

Tall guardians, long scoured clean of paint, with chain

-mail beards and squared-off bodies, planted toes

In low relief. Do I love them for surviving us?

One akpallu brandishes a tasseled mace. The other

Carries his bucket through the garden, touching

Some small device to each open flower. They knew

The finicky, slow task of brushing pollen

Onto pistils takes as great a strength as war.

3

This is my hometown, this is the place

Where I first understood, I thought,

What it really means to look.

Come back, and tucked away between

The fountain and men’s room, one mended

Figure kneels at a sacred tree. Brought out

From Nineveh where, a sign explains,

Iconoclasts would break this sutured image

Of desire if they could. Every fall the storm

Surge rises higher, lapping up the shallow steps

Of the waterfront museum. And where do we spend

Our time and attention, hurting impulse to adore?

Warm light nestles in his pinions and the fountain

Gurgles and clangs when I stoop for a drink.

Bruce McRae

She Wore A Yellow Ribbon

Immortal amaranthine.

Heraldic sable and azure.

Sea-green cerulean.

Mercurial cinnabar.

Flavescent yellow.

Madder yellow,

known as English pink,

that tints medieval manuscripts,

a fugitive colour

made from berries

of the buckthorn bush.

An obsolete colour,

of which the old were fond,

replaced by lightfast dyes.

Made in factories

and opposed to nature.

Such Is Fate

As if a scribble

in a tattered notebook –

that’s who I am.

An odd sock

in predestiny’s bottom drawer.

The goofy-looking kid

wearing broken glasses.

A stolen baby

left on a snowy shore

one Christmas morning.

Found among the bulrushes,

the prince of Nowhere,

a woolen cap my crown.

This pen my golden scepter.

Tom Montag

Three poems from The Woman in an Imaginary Painting

The guard says,

"Do not touch."

Does he mean

the painting

or the woman

in it? He

doesn't say.

I step into

that opening.

*

The light reveals,

but does not speak.

Pigment colors her

skin, but doesn't

share what's within.

The hard line

divides, as it

always does, and

leaves us right

and left. The curves

which shape her

shape our

hope for her.

*

She does not wish

to be made

something of.

The glow of this

moment flecks

her hair with gold-

dust, her eyes with

sky. The soft curves

of this, now of

that, are enough.

If she could

she would sigh.

Mary K. O’Melveny

Lifting Cosmic Veils

At the end of January 2020, NASA ended the work of its Spitzer Space Telescope after sixteen years of receiving images of stars, planets, galaxies and other celestial wonders from its telescope. Using infrared instruments, the telescope operated like night vision goggles, sensing heat radiating from celestial objects. Among its discoveries was that of nebulae IC417, known as “The Spider and the Fly,” several earth-like planets in the Trappist-1 planetary system and the Pinwheel galaxy. The Washington Post, February 4, 2020, E2: “NASA Shuts Down Spitzer Telescope.

I’ve got my eyes on you.

I peered in where no one

has traveled. I stared through

yesterday’s combustions.

The cosmos teases us.

So much history there.

Some of it displeases us—

its violent atmosphere—

but most vistas amaze.

We were watching our past

twist, tease, flicker and blaze.

An artist’s canvas so vast

generations will not

comprehend its visions

until they’re an afterthought.

I’ve recorded collisions

that no one remembered,

seen inside of dust storms,

tracked stars that resembled

spiders and their prey, forms

of fury and feral

interplay that could stop

armies, turn atoms sterile,

cause volcanos to pop

and oceans to appear

where only sand had thrived.

Now no one wants to hear

these tales, see what survived.

My infrared travels

charted new asteroids,

saw planets unraveled,

found pinwheels inside voids.

Maybe you knew my worth,

the truths that I could tell

as I drifted past earth.

Knew it does not end well.

Simon Perchik

(3 poems)

*

You still use rain, breathe in

till your mouth is full

–you can’t jump clear, grow huge

on a sky that has no holes, no Earth

–what did you say, what words

were helped along, holding on to the others

all the way down, facing the sun

though who knows where this thirst

first as ashes, now your own

is kept warm for the whispers

not needed anymore –only rain

as necessary as bending down

comes this close and your voice

more and more feeble, bathes you

lowers you, covers you.

*

You button from the bottom

let these sleeves take hold

reaching across as the silence

that’s used to an old army shirt

slowing your descent into skies

unable to open again though your arms

are already huge, half silk

half the first evening on Earth

–you never see the ground

not because the room is dark

or when was the last time

you circled between your fingers

a single thread that is not white

could pull you back into nothing

nothing! nothing! the nothing

you hear alongside the others

tightening the fit till even the mornings

depend on darkness and cries.

*

What did they underline, first to last

these skid marks never had the time

though nothing you need remains

–the road is used to it, paved

the way rock climbers test for pain

and each handhold eases in more dirt

as if the chalk comes in black

erupts from some invisible callus

that only wants things to move

are important –you blame the Earth

and in its place your arms

for miles with no one left to find.

Claire Scott

Survival

What would happen if we decided to survive more?

from “Dead Stars” by Ada Limon

I have been wondering what

is the message from dead stars would

we want to know what would happen

if we could know could hear if

we could really listen if we

wanted to learn the language decided

to study the stars the seas the earth to

embrace each sentient being in other words to survive

more fully more lovingly more happily more

The Accident

And he knew it was over

not the screeching tires, the sirens, the ER

they would be with him forever

not the TBI, the torqued body, the missing memory

they would last a lifetime

what was over was acting, playing Austin

in True West to a sold out audience in Chicago

what was over were rave reviews in the Tribune

calling his performance sensitive and powerful

what was over was the high after a show

and the desire to do it all again

he took the play out back along with a six pack

and page by page he ripped and shredded and screamed

until the lawn was covered in words

he would never speak

Getting Away With Murder: A Ted Talk

Over fifty percent of murders go unsolved

(e.g. the Smiley Face Killer, Cheerleader

in the Trunk, the Servant Girl Annihilator)

that’s an even bet if you are thinking about it

perhaps considering your Uncle Seth whose

will leaves you a cool million or your neighbor Edna

who lets her dogs use your lawn instead of hers

Only twenty-two percent of trials end

with a conviction on all charges, so maybe

you would be convicted of involuntary manslaughter

which carries a significantly lighter sentence

certainly no lethal injection, swinging noose or firing squad

maybe a few short years with three squares a day

probably worth it to get rid of your calamitous boss

Or you could lure your intended victim to St. Louis,

the city with the highest murder rate in the US

the police so overburdened no one will be assigned to your case

simply offer your Ex a free ticket and a flyer describing

Gateway Arch National Park or Missouri Botanical Garden

where you can meet him with a syringe of Cyanide

that will cause his heinous heart to finally flutter off

Just so you know

Ted Talk delivered by James K. Butcher on June 23, 2020

Barry Seiler

Basic Skills

Up from Ecuador,

Age six, they put him

To work pushing racks

Of designer jeans

In a factory on

The outskirts of Hoboken.

The way he leaned

Into those racks,

He writes, stunted his growth.

He is here to learn

The basic skills. I ask

For five hundred words

Responding to a prompt

Sent by a friend

On the back of a postcard

Of Kafka’s face: Of what

Should a man be properly proud?

His essay reveals deep

Structural flaws,

An inability to link evidence

To ideas, telling errors of expression.

For example: he concludes his essay

By writing: Each week

They gave me dollars and change,

Whatever they liked.

They said They were

Paying me from the books,

From pity cash.

A Late Century Poem

I hear the voice

of Whitman on Napster

Reading a fragment of “America.”

Something about

The adamant of time.

It dawns on me:

What is a dooryard?

It’s late for poetry—

But still—

People go about their business.

They make a living

When they can,

As they can.

The street cleaners sweep

Down the empty streets:

East to the Hudson,

West to the Emergency.

I hear the song of glass on lid

Under my window

As someone lifts the empties

For spare change.

Poetry Class

Stephen Stepanchev, 1915-2017

Once the airplane is off the ground,

You taught us,

You don’t need the runway.

And so I cut, cut, cut

To keep myself aloft.

Years later I learned I could add.

All I needed was a simple conjunction

Now and then to keep the lines moving.

And so it has been: cut and add,

Add and cut until I’ve had enough.

You can make a life of that.

David Spicer

Our Sunday Drives

My sister, brother, and I stayed quiet as the dead possums

on the South Dakota highway while my father yelled

at the windshield, That bald-headed bastard cut me off!

My mother said, grinning, Judge not lest ye be judged.

After church my father drove up and down the roads

in one of the many dying cars he had owned, the three of us

waiting for the moment he’d speed up hills—laughing,

hands off the wheel—then down, as our stomachs rushed

to our throats. For a couple of years we’d look forward

to jumping into the junker, going a different way

than the week before. We always hoped, before heading

back home, he’d stop at the hamburger shack on the outskirts

of the forgotten-name town, where my parents shared a dime

hot dog and we licked our own grape, cherry, or lime lollipop.

Tim Suermondt

Du Fu Was Right

I set myself some tasks

and I finished every one—

the satisfaction, however,

was disappointing, not nearly

as grand as I had imagined.

Later, I set myself more tasks,

finishing not a one—

and how remarkable I felt.

“I’ve never seen you so happy,”

my neighbor said. “What happened?”

“Nothing, nothing, nothing…”

those nothings rolling off my tongue

like lyrics of a hit Broadway show

or a soundtrack of a part of Paradise—

maybe, maybe both, dancing.

What We All Think

Never comes to exact fruition—

sometimes we do come close, sometimes

we don’t come anywhere near

and it can all be gloomy black and white

like Weimar, despite every street adorned

with dance halls and jugs of beer.

But when a woman on the boulevard waves

to you, even if she meant the gesture

for someone else, you can’t help but think

everything, everything will be wonderous

now and—in that moment—be forgiven

for ignoring the men in half shadows

who carry torches and howl like wolves.

Casablanca

Birds fly from the eucalyptus trees

in the hills over the Hassan Mosque

and the modern buildings of business,

smattering of Art Deco to spice things up

and the swabbed sun bathing the port.

Along the quay rappers are performing,

getting the attention of the birds who stop

in mid-air to listen, flying down as close

to the crowd as they dare, flapping

their wings to the beat, the shovel of words.

Wasting Time on a Winter’s Day

I won’t be needed for a while—

empires will still rise and fall without me.

Simmering soup and sitting with my wife

on the couch, watching geese in the white

misted air fly by the window—sloth

of the most beautiful kind. Forecasters

say it might be a long winter. Good.

Reed Venrick

Water Without Borders

Why deny the will of the water? Soft,

Hard, salty, even when our scientific

Time measures lifelines. Do dive

The rainbow reefs miles offshore, only

Winds and waves beyond, where storms

Are birthed inside concentric mandalas

Of turbulence and seasons of soaked calendars,

Hundred year flood plains forecast seas filling

Salt marshes, while lilies sprout in abandoned

Trash and garbage on the trails of jogging

Paths. When blown-down royal palms

Are the only shade on earth, all along

The no-exit Gulf, where the frond limb hangs

Limp and long across the exhausted swing

Of changing winds, and when the twist of a invisible wrist

Turns the water on, crushing condos of Miami,

Where streets turn to sewer lines, and once

Paved I-95 now a canal running an artery

Out to sea to fill the spirals inside Nautilus

Shells. No—we don’t know the schedules

Of the flighty fates, but we know the waters

And tsunamis wait for no human kind, and when

The invisible hand, and the nautilus mind decides

It’s time, the seas of salinity and sublimity will submerge

Not just pines and fishtail palms, but mountains

Inside oceans higher than Everest, and when

The tidelines vanish, and all oceans of the world

Join to become one, we remember the waves rising

Above the last lone palm on a Sahara dune,

So that the beginning of the end may begin again.

Nuit Blanche

Asleep too soon, awake too early,

A nightmare in a holding pattern,

Speaking with Saint Exupery, my co-

Pilot mind—the night is timeless in odd, so

Switch eyes side to side, and unlike

the frantic-change-driven day, you know

This perfection of existence between

Three and four a.m., but the deadly “swishing”

Noise of a fighter early above this island key,

Diving into the inky night, they’ll be over

The Bahamas before I return from the bathroom—

When a breeze jolts my windows, and while

I twist inside the window frame far-away,

I feel the chill fog of dawn creeping in, like

A glades panther, where I lie near the exit

Of this world, connected still to the roll of ailerons,

Yet the shocking knocking that bangs my ear,

Just when I’m I’m drifting off, again,

Clinging to a broken cable, slicing my leg raw,

The silence roaring and blood in my mouth,

A mumble to the careless gods in the clouds,

But only the flashing back to a stall, and

And a sudden spinning fall, nose down like

A nightmare scream—again, what might have

Been and how in time to fill horizontal

Spaces, a lost space to redeem, and

A time warp caught me supine at 3 a.m.

No, I do not remember the path I took

After the aircraft slipped into auto-pilot,

And now, though I forget where I am,

I see I recline on the leeward side, glancing

At my compass once, twice, thrice—true north

Keeps me straight—after all I shifted into

Another plane-line in that crash many years

Ago, and yet between 3 and 4 a.m., I am still

Here in my hammock—hanging on the horizon line.

Erin Wilson

Drift

Wind and the power of wind.

Wind over fields of snow

and wind off fields of snow.

Wind picking up

and drying every particle of snow

every second and blowing snow,

except wind a thousand thousand times wind

drying a thousand grains every second

and casting them across the road.

Wind and the casting of snow obliterating the road

except for the wolf prints I now follow.

Scarf up over my nose. Hat down over my brow.

Only my nose hazards forward before my body,

my gaze but a gash,

narrowly restricted.

I walk through snow.

The claws of the wolf tracks proceed

in the same direction.

Danger, this wolf? Hardly.

One hour ago you fashioned me,

viscous honey.

You rolled me on the marver.

You put your mouth to me,

pulled me into a long ribbon.

Blue and white glass.

One hour ago your heat — elongation.

Blue and white glass.

One hour ago, fusion.

The most elegant of fluted glass.

And then — shatter.

Once we recovered we managed dumbly,

two dunderheads, a duo of dullards,

to wind our mouths once again

around language, the throat's bottle.

What now, someone asked.

Now we blow, now we blow apart

continuously continuously

we blow apart and apart

and away like snow.

In Concert

I'm crossing

the bridge

as they swoop

by me

in tandem,

the first two

spring geese.

There is

still ice

along the river,

but the black vein,

whether

I see it move

or not,

is maneuvering

up the centre,

fluid.

I was in a bad mood

before I saw the geese,

was feeling

the effects of

the annihilation

that inhabits one's soul,

tail-end of every winter,

before the first green thing

invigorates.

But these geese,

they gyre in on

winds

that can't be seen,

and they turn,

winding

themselves

in utter concert

toward the river,

curving,

correcting

and arching more,

bewitched arrows

bent to strike

the target

of this spinning world.

HSR Archives

Submissions

Contact Us

Commentary on HSR

Hamilton Stone Editions Home

Our Books